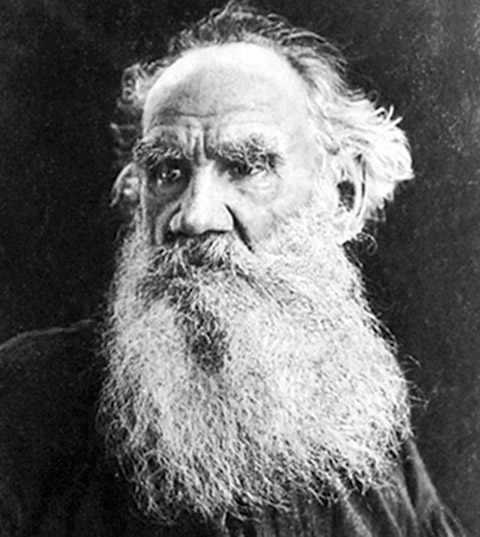

It's strange that the great Russian writer Leo Tolstoy is rarely remembered as a pacifist, because this passionate belief system was the center of his amazing life and work. He defined himself as a pacifist in no uncertain terms. He didn't title his novel Vonya i Mir (War and Peace) because he thought the choice ought to be a toss-up.

Why is he not often remembered as a pacifist today? Perhaps the twists and turns of Russia's turbulent 20th century have tempted too many communists and anti-communists to fight over the great 19th century genius's philosophical legacy, and to try to claim him for one side or the other. He belonged to neither camp. He was a Christian pacifist, and a fully consistent, committed and clear-thinking one. He devoted his entire life to the cause of peace.

Born in 1828 into an aristocratic family, young Leo Tolstoy fought for Russia in the Crimean War and turned this experience into a sensational literary debut, eventually published as The Sebastopol Sketches. But the life of a fashionable St. Petersburg literary socialite did not appeal to this man's far-reaching mind, and he followed his early success by departing on a difficult journey of spiritual exploration similar to the journey's he described in the lives of his two main characters, the brainy and sometimes foolish Pierre Bezukhov of War and Peace and the idealistic, lovestruck Constantin Levin in Anna Karenina.

Those two novels are considered Tolstoy's two masterpieces, but it was his shorter The Kingdom of God Is Within You that would inspire revolutionary new ideas in the life of a young Indian lawyer working in South Africa named Mohandas Gandhi. Gandhi would soon create an experimental community in South Africa called Tolstoy Farm. Tolstoy's own estate Yasnaya Polyana was also a functional experimental community, and the great thinker remained active and engaged with the outside world from this home until his death in 1910.

Colm McKeogh said the following in his book Tolstoy's Pacifism:

Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) was the most influential, challenging, and provocative pacifist of his generation. The most famous person alive at the dawn of the twentieth century, his international stature came not only from his great novels but from his rejection of violence and the state. Tolstoy was a strict pacifist in the last three decades of his life, and wrote at length on a central issue of politics, namely, the use of violence to maintain order, to promote justice, and to ensure the survival of society, civilization, and the human species. He unreservedly rejected the use of physical force to these or any ends. Tolstoy was a religious pacifist rather than an ethical or political one. His pacifism was rooted not in a moral doctrine or political theory but in his straightforward reading of the teachings of Jesus as recorded in the Gospels.

Despite his fame, Tolstoy’s pacifism remains insufficiently studied. A hundred years after his death, Tolstoy is a figure unfamiliar in political science, encountered, if at all, as the author of hortatory quotations on the wrongness of political violence or of allegiance to the state.

Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You was itself a response to the feedback the author had received on an earlier philosophical work, What I Believe. The following quotation is from this earlier work:

Every doctrine of truth is a dream for those who are in error. We have come to such a state of error that there are many among us who say, as I did myself formerly, that this doctrine of Christ is chimerical because it is incompatible with the nature of man. It is incompatible with the nature of man, they say, to turn the other cheek when he has been struck; it is incompatible with the nature of man to give up his property to another – to work, not for himself, but for others. It is natural to man, they say, to protect himself, his own safety, that of his family, and his property – in other words, it is the nature of man to struggle for life. Learned lawyers prove scientifically that the most sacred duty of a man is to protect his rights – that is, to struggle.

We need only for one moment to cast aside the idea that the present organization of our lives, as established by man, is the best and most sacred, and then the argument that the teaching of Christ is incompatible with human nature immediately turns against the arguer. Who will deny that it is repugnant and harrowing to a man’s feelings to torture or kill, not only a man, but also even a dog, a hen, or a calf? I have known men, living by agricultural labor, who have ceased entirely to eat meat only because they had to kill their own cattle. And yet our lives are so organized that for one individual to obtain any advantage in life another must suffer, which is against human nature. The whole organization of our lives, the complicated mechanism of our institutions, whose sole object is violence, are but proofs of the degree to which violence is repugnant to human nature. No judge will ever undertake to strangle with his own hands the man whom he has condemned to death. No magistrate will himself drag a peasant from his weeping family in order to shut him up in prison. Not a single general, not a single soldier, would kill hundreds of Turks or Germans, and devastate their villages – no, not one of them would consent to wound a single man, were it not in war, and in obedience to discipline and the oath of allegiance. Cruelty is only exercised (thanks to our complicated social machinery) when it can be so divided among a number that none shall bear the sole responsibility, or recognize how unnatural all cruelty is. Some make laws, others apply them; others, again, drill their fellow-creatures into habits of discipline – i.e., of senseless passive obedience; and these same disciplined men, in their turn, do violence to others – killing without knowing why or wherefore. But let a man even for a moment shake off in thought the net of worldly institutions that so ensnares him, and he will see what is really incompatible with his nature.

— Leo Tolstoy, What I Believe